Editorial, Originally Published: 8 March 2006

I got an urgent call the first of this month [March 2006] from an editor at one of London’s larger newspapers, the Telegraph: could I write some commentary about Cherie Booth’s new book, and could I have it to them in plenty of time for them to include it in the “News Review” section of their Sunday (5 March) edition?

Cherie Booth is not simply a Q.C. — a “Queen’s Counsel”, an especially high-ranking barrister who is appointed to work on behalf of the Crown — she also happens to be the wife of Tony Blair, who is (to use his full title) the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, First Lord of the Treasury, and Minister for the Civil Service. And leader of the Labour Party.

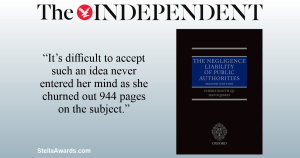

Booth’s new book is a 944-page, 145-pound law textbook titled The Negligence Liability of Public Authorities. (Note that 145 pounds is not how much the book weighs, but how much it costs; GBP145 is about US$252.) It has brought quite a bit of debate about whether the book not only caters to a growing “compensation culture” in Britain, but whether it will encourage more lawsuits — especially frivolous lawsuits — against public (government) entities. That’s where I came in: the Telegraph wanted me, as the author of the True Stella Awards, to comment on it from my perspective.

I indeed wrote the piece and got it to them in time, but it didn’t appear in the Sunday paper. When I inquired, the reply from the editor was, “Well we were all set to run, and then at the very last minute we had to run a moving tribute piece to someone who had died. I am afraid this is the problem with being a news-reactive section, we have to clear the pages at the 11th hour sometimes when something like this happens.”

I hate when that happens, and she didn’t even mention who it was that died. But I didn’t work on this for hours for nothing; if the Telegraph won’t publish it, then I will, and hope it’s seen by readers in Britain — and Australia, and….

-v-

Cherie Booth’s How-to Manual

by Randy Cassingham, Author

The True Stella Awards (Dutton, 2005)

Cherie Booth Blair’s new book is bringing with it renewed fears of an explosion in frivolous lawsuits against public entities. Ms. Booth seemed shocked that her legal how-to book might actually result in more lawsuits. When asked if it was a guide to help plaintiffs “milk authorities,” Ms. Booth replied, “I’d never thought of it like that.” It’s difficult to accept such an idea never entered her mind as she churned out 944 pages on the subject.

Her husband got it half right. “We cannot guarantee a risk-free life,” Tony Blair said in a speech last May, urging Britain to “replace the compensation culture with a common sense culture.” Yet at the same time, he claimed that “the most outlandish cases that are brought are dismissed. But their headlines live on [and] create a myth” that alarms the ignorant public, which doesn’t know that things are well in hand, safeguarded by people such as his wife.

The Sophie Amor case isn’t a myth. Amor says she was bullied in her Wales school as a girl. “I used to dread going in every day,” she said, her words echoing what so many children think of school. “I wanted to fade into the background but it felt as though everyone was staring at me — jeering and laughing, pointing at me.” At 23, she sued Torfaen Council, which last month allowed its insurer to settle for 20,000 pounds “to resolve the matter and to minimise costs,” a Council spokesman said, even though “we have not accepted liability.”

But maybe that’s not outlandish enough for the P.M. When Carl Murphy was 9 years old, he was trespassing at a warehouse near Liverpool and broke through the roof of the building. He fell 40 feet and suffered a skull fracture. When he turned 18 last year he sued the building’s owner, claiming that had the site had a better security fence to keep him out, he wouldn’t have been injured. “The papers just call me a yob and a thug because I’ve been done for robbery and assault but those were just silly stupid little things, like.” Murphy was awarded 567,000 pounds. He said he’d spend his windfall on a “flash car” and “a big house so I have a place to live with me mum when she gets out of jail.”

The result of tort “myths,” Mr. Blair said, is that “public bodies, in fear of litigation, act in highly risk-averse and peculiar ways” — and called such fears unfounded.

Yet a 2003 study found that the previous year, Nottingham Council paid out 1.5 million pounds in compensation over pavement tripping claims, but only put 1.2 million pounds toward actually fixing the pavements. The same year, Cardiff paid out 1.7 million pounds in pavement claims, three-quarters of its 2.2 million pound roads budget.

All told, Britain-wide the payoffs total 500 million pounds a year from taxpayers’ turned-out pockets. Perhaps the Blairs think that’s small change compared to the US$550 million (about 314 million pounds) paid out in claims each year by just one American city: New York. Imagine the crisis if London had a bill that large. Or don’t imagine it, just wait — you’ll get there.

Blair’s mention of the “myths” of litigation is particularly galling to me. For several years I have been sounding an alarm about the increasing abuse of the civil court system in the United States via my web site, StellaAwards.com. Few seem to know who the site’s namesake, Stella Liebeck, might be, but when I explain she was the 79-year-old New Mexico woman who, in 1992, spilled McDonald’s coffee in her own lap, sued the fast food chain over her resulting injuries, and won $2.9 million (about 1.66 million pounds), virtually every American says “Oh, HER!”

The name Stella spread throughout America, even among those who didn’t make the connection; it’s applied like a label to any frivolous lawsuit, actual or imagined, that comes to the public’s attention.

Yet what really caught the public imagination was an Internet “meme” called the Stella Awards — a brief synopsis of a half-dozen cases that seems to illustrate a system gone completely mad, which spreads annually by email. The ultimate case was supposedly filed by a “Mr. Grazinski” who, we are told, bought a Winnebago motor home. On his way home from the dealer, he engaged the cruise control and stepped into the rear to make coffee, as if motor homes come complete with one’s preferred brand of grounds and filters.

As the story goes, the driverless Winnie crashed and the hapless Grazinski sued, claiming the manufacturer failed to warn that a cruise control is not an automatic pilot allowing the driver to go on a walk while motoring. He supposedly won both $1.75 million and a replacement motor home.

That case is the “winner” of the Stella Award email roundup every year. It is, however, not real. Like the rest of the email, it’s a completely fabricated urban legend, with the only change each year being the date at the top.

As the author of a weekly column recounting strange-but-true stories from around the world, my readers kept sending me the Stella email, begging me to write about them because they were so stupid. Unfortunately, the only stupid part about them is that people were willing to believe these myths were true — which says something quite terrible about what Americans think about their civil court system.

Which left the question: is there a problem with frivolous suits, or not? Just like Mr. Blair, the Association of American Trial Lawyers, whose members represent plaintiffs in tort cases, proclaimed that the very existence of the Stella Awards myths was somehow proof that there was no problem with frivolous lawsuits in the United States. If Internet wags had to make up cases, their theory went, there must not be any real cases to talk about.

In 2002 I set out to prove that there were indeed plenty of stupid-but-true cases of lawsuit abuse in the U.S. I found them easily, publishing scores of summaries under the Stella Awards moniker that the public had gotten so used to, but adding one word: I call them the True Stella Awards.

The real cases quickly gained attention: tens of thousands are registered to get the case write-ups by email as they’re issued, and last fall Dutton issued the True Stella Awards book. Within days of publication it broke into the top 50 on Amazon’s nonfiction best-seller list.

Yes, many are amused at the sheer stupidity of the cases presented, but Americans are truly worried about where this is all going, what such cases mean about us, and — yes — whether we now live in a compensation culture.

It’s a fair question. In 2002, lawsuit costs represented 2.33 percent of America’s Gross Domestic Product, up from 1.54 percent in 1980. In 2001, the latest year such statistics are available, America’s population grew by 1.1 percent, the consumer price index was up 5 percent, and the GDP was up 7.6 percent. Tort costs? Up 14.3 percent.

What Britain Has to Look Forward To

While our “lawsuit industry” amounts to well over 2 percent of our GDP, the lawsuit portion of United Kingdom’s GDP is estimated to be less than 1 percent, so congratulations are due you. But here’s what you have to look forward to as your litigation crisis grows to U.S. proportions. All of these are real court cases detailed in my book:

- Robert Paul Rice, a prisoner serving time in Utah on weapons, theft and burglary convictions, claimed his Constitutional rights were violated: the freedom of religion. Sounds serious until you learn that his religion is “Druid Vampire” and the prison is keeping him from his “vampiric sacrament” (drinking blood), not to mention his religious requirement for sexual access to a “vampress.” Yet when he signed into prison two years prior, Rice listed his religion as Roman Catholic.

- Marissa Imrie was just 14 when she caught a cab and rode 50 miles to San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. She promptly jumped off, killing herself. Her mother sued the bridge authority, complaining it should have built an “effective” suicide barrier as the bridge is well known as the world’s most popular suicide spot. Stretching credulity, the suit claimed that the lack of such a barrier was a violation of the girl’s Constitutional right to life. If that weren’t enough, the suit argued the mother’s rights were also violated: her “Constitutional right of familial association.”

- Police departments in America are favorite targets. Officers in Ohio confronted Christopher Sample, 27, as he burgled a building. Despite being surrounded, Sample suddenly reached into his coat; officers, thinking he was reaching for a gun, opened fire. Sample survived to serve six months in prison. When he was released, he sued the police department for shooting him, even though the officers’ actions were ruled justified after lengthy investigation.

- Police in South Carolina received a report of a vehicle trying to run down a pedestrian. When officers arrived the suspect vehicle sped away, and they gave chase. In his attempts to elude the officers, Ron Brown, 23, drove into a marked road construction area and drove off the end of an unfinished bridge. His father sued for wrongful death, naming not only the city and its police department, but also the construction company, the state department of transportation, the apartment complex where the chase started, and the person who called the police to report the attempted murder.

- Cities are emulating the worst of the trend by trying to turn the tables. A California police officer had the suspect from a minor disturbance handcuffed in the back of her patrol car. When the man started to kick at the car’s windows, the officer decided to subdue him with her Taser. Incredibly, instead of pulling her stun gun from her belt, she pulled her service sidearm and shot the man in the chest, killing him instantly. The city, trying to protect its budget, says the killing is not the officer’s fault, but rather “any reasonable police officer” could make such a mistake, slurring every police officer who actually paid attention to their training. The city filed suit against Taser, arguing the company should pay for any award from the wrongful death lawsuit the man’s family filed against the cop.

- Our children are learning the lawsuit lesson well. Mark Edmonson was excelling at his high school: Early in his senior year, he had excellent grades, got a perfect score on his college entrance exam, and was a National Merit finalist. He applied to the University of North Carolina and received a letter of acceptance. The university’s letter clearly warned, “your enrollment will depend upon your successful completion of your current academic year…. We expect you to continue to achieve at the same level that enabled us to provide this offer of admission.” But Edmonson’s grades slipped badly, and he failed one class entirely. When the university rescinded its acceptance, he sued, claiming the letter was a “contract” that it failed to fulfill.

- Cole Bartiromo, a high schooler in California, made over $1 million in the stock market, but federal watchdogs made him pay it all back: he gained his profits, they said, via fraud. Bartiromo played baseball at school, but after his fraud case broke he was no longer allowed to participate in extracurricular sports. Bartiromo thus filed suit against his public school, reasoning that he had planned on a pro baseball career but, because he was kicked off the school’s team, pro scouts wouldn’t be able to discover him. His suit demanded the school reimburse him for the great salary he would have made in the majors, which he figured at $50 million.

Things are just as bad in the private sector:

- In 1997 Bob Craft, then 39, of Hot Springs, Montana, legally changed his name to Jack Ass. After the TV show and movie Jackass generated huge profits, Mr. Ass claimed the show’s idea was “plagiarized” from him, infringed his trademarks and copyrights, and demeaned, denigrated and damaged his public image — his good name, if you will. No attorney would take the case, so he filed suit on his own against the producers demanding $50 million in damages.

- Fr. David Hanser, 70, was one of the first Catholic priests to be caught up in the sex abuse scandal. In 1990, he settled a suit filed by one of his victims for $65,000. In the settlement, Hanser agreed not to work with children anymore, but the victim later learned that Hanser was ignoring that part of the agreement. The victim appealed to the church, asking it to stop Hanser from working near children, but the church would not intervene. When the outraged victim went to the press to warn the public that a pedophile priest was working near children, Hanser sued him for his $65,000 back because the victim violated his part of the deal — to keep the settlement secret.

- Michelle Knepper of Washington state picked a doctor out of the telephone book to do her liposuction, and went ahead with the procedure even though the doctor was not a plastic surgeon. After having complications, she complained she never would have chosen that doctor had she known he wasn’t Board Certified in the procedure. So she sued …the telephone company!

It’s true that many such cases are lost, even in the U.S., but Michelle Knepper, who chose her doctor based on his telephone book ad rather than glancing at the certificates hanging on his wall, prevailed: she was awarded $1.2 million, plus $375,000 for her husband for “loss of spousal services and companionship.”

Even when the plaintiffs are tossed out of court at an early stage, the damage is significant. The U.S. has no loser-pays rule, so every defendant is out of pocket for their defense. Judges must give every plea, no matter how silly, a proper hearing, slowing down the system to nearly a halt; even simple cases tend to take 3-5 years to conclude.

It’s difficult to slow such a juggernaut: U.S. lawyers earn $50 billion in legal fees per year, with a significant portion coming from a hefty percentage of lawsuit winnings. It’s hard to get “don’t worry, be happy” Americans to act, but in 2006 it’s estimated that the lawsuit load on the average American citizen, represented by increased insurance premiums and general goods and services, will exceed his income tax bill. Maybe, finally, that average citizen will take notice of his draining wallet, and angry Americans can be a potent force for change. But for now, most simply shrug and say, “What compensation culture?” — just as the British are doing.

Tony Blair was right the first time: We cannot guarantee a risk-free life. Britain — and America — indeed must derail the compensation culture in favor of a common sense culture, and save compensation for those who are truly harmed.

Sources

- The case about Stella Liebeck is necessarily summarized; there’s more to the story on my web site. The faked annual cases are summarized here.

- Most of the figures cited are from my True Stella Awards book, published in November by Dutton.

- For those who aren’t familiar with my strange-but-true news column, you can find it at thisistrue.com.

- Note: Links to the cases discussed were added for this 2022 repost.

My 2022 Thoughts on the Case

Quick! Write 2,500 words for us on a really short schedule! (And we won’t bother to tell you it got booted for breaking news.) That hoodlum’s use of “yob” works well here.

Almost on cue, a few weeks later a British case hit the international news wires: Sue Storer, 48, a deputy headteacher in Bristol, complained that she was “forced” to sit in a chair that made “farting sounds” as part of a harassment campaign against her because she was a woman. She resigned her 48,000 pound-per-year art teaching job and filed a complaint to the British equivalent of the EEOC: an employment tribunal. She demanded 1 million pounds (US$1.8 million) in compensation.

One thing you can say for Britain: things seem to move more quickly there; her hearing was held in late March after only being filed six months before, and just weeks after the news hit the papers the decision was announced. The school’s headteacher had told the tribunal, “I would have expected any member of the leadership team and a deputy headteacher, who has the authority on my absence to run a school, to have the wit and initiative to sort it out.”

In other words, she had the authority to get her own damned chair, but failed in even that most basic task. The tribunal agreed that “flatulent chair” or not, there was no campaign to harass her. It denied her claim.

Sources: “‘Flatulent Chair’ at Bottom of Teacher’s Sex Bias Claim”, London Times, 22 March 2006 (reporting on the claim), and “Deputy Head Loses £1m Compensation Claim over ‘Farting’ Chair”, London Guardian, 10 April 2006 (reporting on the dismissal).

Letters

Of the flurry of short case write-ups to finish up 2005, one brought more comment than the rest combined: Something for Nothing, Defined was about a woman in West Virginia who took out an insurance policy on her car, and paid the premium with a bad check. The company thus canceled her policy as of the issue date, and notified her of that. That is, she didn’t pay, so her coverage was void from the start.

But in the meantime, she had been in an accident; she sued the insurance company demanding it cover her accident, even though she never made her payment good. (I say that firmly because that’s the crux of the case.) The case made it all the way to the state supreme court, which ruled 4-1 that the insurance company must cover her; the one justice strongly opposed the verdict.

With that, the letters:

Mark in Pennsylvania: “I am an insurance agent in Pennsylvania, and I know that most insurance companies put a statement on their applications which states: ‘The rendering of a valid and negotiable down payment is a condition of coverage. Payment means cash, certified funds, credit card, or check. If the down payment is returned unpaid by the financial institution, the policy will be rescinded and there will have been no coverage.’ (This is directly from one company’s application.) So, Stephanie would have had to have signed the application, and it should have that, or a similar, statement.”

I wish my source covered that detail, but it didn’t. It wouldn’t surprise me one bit if there was similar language, though — and for an insurance contract, that’s pretty darned clear language.

Alan in Scotland: “I don’t agree with your take. If for some reason the payment for your insurance doesn’t go through surely it is incumbent on the insurance company to get in touch with you and advise you. What if the bank made a mistake? What if they didn’t send a letter? What if you had paid it but the insurance company’s records were wrong? Would you still feel the same if she ran into your car and then you discovered she wasn’t insured? I doubt it.”

Yes, the insurance company should notify me in a timely manner. I wish my sources were very clear on exactly what happened when, but it wasn’t, so I can’t comment on how timely the notice was.

But notice surely came from two directions: the insurance company and the woman’s bank. So on to the questions I can answer: What if the bank made a mistake? Then they would be liable. What if the insurance company didn’t send a letter? Then I’d probably agree that they should cover the accident, but only once she paid her premium. What if the insurance company’s records were wrong? Then they would definitely be liable. What if she hit me? I’d be angry, but I wouldn’t demand that an insurance company be forced to cover someone who didn’t pay their premium; that’s where chaos begins.

Let’s be real here: where will this case lead? In West Virginia, at least, it will definitely lead in two directions: First, people won’t be able to pay their premiums (especially their first premium) by check, which will certainly be an inconvenience to honest people, and increase processing costs (which will be passed on to the clients).

Second, the insurance companies will surely add language to their contracts that coverage doesn’t start until the payment clears (or for 15 or 30 or more days), which means people won’t be able to get insurance coverage unless they bring in cash, cashier’s checks, or other guaranteed forms of payment, putting huge burdens on honest customers.

And for what? To appease a woman who never paid her premium, and thus does not deserve to be covered? Why?

Here’s the best answer I’ve seen so far:

Kevin, an attorney in West Virginia: “The statutory law in W.V. is the issue, and the Court ruled in the manner prescribed by law. Syllabus points 3 and 4 from the Court explain the issue clearly and succinctly: ‘(3.) Under W.Va. Section 33-6A-1 [2000], if an insurance company chooses to issue a new policy of automobile liability insurance to an insured, and the insured fails to pay the initial premium or otherwise provide necessary consideration for the new policy, the insurance company may cancel the policy. However, the cancellation of the policy can take effect no earlier than ten days after notice of the cancellation is provided to the insured. (4.) Where there has been an invalid cancellation of an automobile liability insurance policy, the policy remains in effect until the end of its term or until a valid cancellation notice is perfected, whichever event first occurs.’

One might ask why the Legislature would create such a law, but the reason is simple: If a policy is new and a claim is made before the insurance company cashes the check, the insurance company (prior to the law) would return the check to the person and void the policy. The law requires the insurer to provide notice of cancellation, and provides the insured person with a grace period of coverage to prevent insurers from ducking claims. The law is clear on the issue, and the Court ruled in accordance with the law.”

Meanwhile, the British textbook pioneered by Ms Booth is in its second edition. I will be interested to hear from U.K. readers about the state of their courts after 16 years.

- - -

Email Subscriptions

No new cases are being published, so please don’t try to submit cases.

My Flagship Email Publication This is True continues to come out with new stories every week. It’s “Thought-Provoking Entertainment” like Stella, but uses weird-but-true news items as its vehicle for social commentary. It is the oldest entertainment newsletter online — weekly since 1994. Click here for a This is True subscribe form.

A hidden cost of frivolous cases is the efforts taken to “lawsuit proof” products. I saw a box of Chex cereal that had the usual “enlarged to show detail” disclaimer. This went a step further because the box also had a photograph of some delicious Chex Party Mix. So they had to add another disclaimer: “Cereal inside box. Recipe for party mix on side panel.”

Sometimes I can’t help asking myself what happened to make a particular disclaimer necessary. The one about not ironing clothes while wearing them is obvious, others not so much.