Stella Case No. 015, Originally Published: 6 November 2002

In 1997, MCA Records released the song “Barbie Girl” by the Danish group Aqua. To the dismay of Mattel Inc., owner of the cash cow Barbie doll (and its registered trademark), the song quickly became a smash hit, both in the U.S. and abroad.

The lyrics were fairly banal, at least at the start: “Hiya Barbie! / Hi Ken! / You wanna go for a ride? / Sure, Ken! / Jump in! / Ha ha ha ha!” But the chorus — oh, the chorus: “I’m a Barbie girl, in my Barbie world / Life in plastic, it’s fantastic / You can brush my hair, undress me everywhere / Imagination, life is your creation.”

And then there were lines like “I’m a blonde bimbo girl, in a fantasy world / Dress me up, make it tight, I’m your dolly”, “Kiss me here, touch me there, hanky-panky”, and “You can touch, you can play / You can say ‘I’m always yours’.”

Mattel was not amused: it filed a federal lawsuit charging trademark infringement. Mattel argued the song would “create a likelihood of confusion in consumers,” a standard claim in any trademark infringement case, and that the song “diluted” Mattel’s Barbie trademark by “diminishing the trademark’s capacity to identify the Mattel doll” and by “tarnishing the doll’s good name, and thus the trademark, with risqué lyrics that were inappropriate” for the target market — young girls.

It didn’t help that the song’s catchy tune made it easy for those same young girls to memorize every word.

Trademarks are important: they tell consumers that a product comes from a particular source; misleading consumers into thinking that another product was produced by the trademark holder is infringement, unfair trade, and dilution (which courts define as the “whittling away of the value of a trademark”).

To guard against such claims, MCA had included a disclaimer on the release which noted the song was “social commentary not created or approved by the makers of the doll.” But such a disclaimer was “unacceptable,” a Mattel spokesman told reporters. “It’s akin to a bank robber handing a note of apology to a teller during a heist, [which] neither diminishes the severity of the crime, nor does it make it legal.” He said the Barbie Girl song lyrics thus constituted “theft of another company’s property.”

MCA didn’t take that legal maneuver lying down. “Bank robber”? it bristled. “Heist”? “Crime”? “Theft”? Them’s fighting words: MCA filed a countersuit claiming libel.

In hearing the case, the Federal Circuit Court ruled that the song indeed “diluted” Mattel’s Barbie trademark, but pointed out there are three exclusions that allow such dilution: comparative advertising, news reporting, and commentary and noncommercial use. “MCA used Barbie’s name to sell copies of the song,” it ruled, but it was “noncommercial” because the song was clearly “social commentary on Barbie’s image and the cultural values she represents.” In other words, the song was parody and commentary, as allowed by the Constitution’s free speech guarantee in the Bill of Rights.

“Parody and satire have to be excluded” from trademark dilution statutes, says Florida trademark attorney Mark Stein, commenting on the case. Otherwise, the entire Federal Trademark Dilution Act would be declared unconstitutional on First Amendment grounds.

“The parties are advised to chill,” scolded Judge Alex Kozinski of the U.S. Court of Appeal, which unanimously upheld the decisions of the circuit court in throwing out both Mattel’s trademark infringement claim and MCA’s libel claim. “Simply put, the trademark owner does not have the right to control public discourse whenever the public imbues his mark with a meaning beyond its source-identifying function.” Judge Kozinski pointed out that Barbie was originally modeled on a “German street walker” which Mattel turned into a “glamorous, long-legged blonde” which has been called both “the ideal American woman and a bimbo” — and that “with fame often comes unwanted attention.”

“The song pokes fun at Barbie and the values that Aqua contends she represents,” Judge Kozinski wrote in his opinion. Speech which “does more than propose a commercial transaction” is “entitled to full First Amendment protection.”

Mattel might have been proud that they could turn a doll inspired by a foreign prostitute into an American icon that artists want to talk about. Instead, they sued over an obvious parody and got the only reward rightfully theirs: a Stella Award.

Sources

- “MCA Records Wins Barbie Battle,” National Law Journal, 6 August 2002.

- “Mattel v. MCA Records, et al,” U.S. Court of Appeal for the Ninth Circuit Opinion No. 98-56453, 24 July 2002

Case Status

Dismissed. You can hear the song (in its official video) below.

My 2020 Thoughts on the Case

Probably partly thanks to Mattel suing, “Barbie Girl” went multi-platinum. Aqua sold an estimated 33 million albums and singles (of all their titles, not just BG), making them the most profitable Danish band ever.

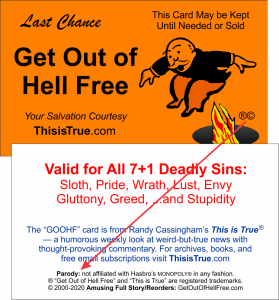

I’m actually a bit surprised that I didn’t talk about a similar case at the time: my own Get Out of Hell Free® cards. Notice the registered trademark symbol? Yep: I was granted that (and a federal copyright registration) despite similar saber-rattling from Hasbro.

Every card has a disclaimer very similar to the one MCA Records used: “Parody: not affiliated with Hasbro’s MONOPOLY in any fashion” — as dictated by my intellectual property attorney …just like MCA’s disclaimer certainly was.

Certainly, “Parody and satire have to be excluded” from trademark dilution statutes to stay on the right side of the Constitutional guarantee of free speech. “Simply put, the trademark owner does not have the right to control public discourse whenever the public imbues his mark with a meaning beyond its source-identifying function,” the judge in the case said, which is how Aqua, and I, get to do social commentary with the aid of trademarked words and symbols.

Letters

Several readers wrote in shock (shock I tells ya!) at my contention that Barbie “was originally modeled on a ‘German street walker’.” [Aside: I considered a tangent here about how the concept of prostitution keeps coming up when talking about lawyers and such, but to save a lot of time: “Incorporated herein by reference.”]

But yes, dear readers who grew up in the 60s and later and are now mothers yourselves, your (and your little girl’s) favorite doll was indeed inspired by a German doll for men called “Lilli”. The original Barbie even was dressed similarly to Lilli — Barbie inventor Ruth Handler had picked up several of the dolls in Germany in 1957 and brought them to fellow Mattel founders to try to convince them that such a doll would have a market here. (It did: it’s estimated that 172,000 Barbies sell per day. So now you know why Mattel would do anything to keep the leaks out of that cash geyser!)

Lilli (the doll) was modeled after a cartoon character in Bild (a German newspaper). As Salon magazine put it in a 1997 feature they titled “The Littlest Harlot” [link removed: apparently no longer online], “A professional floozy of the first order, Bild Zeitung’s Lilli traded sex for money, delivered sassy comebacks to police officers, and sought the company of ‘balding, jowly fatcats’…. While the cartoon Lilli was a user of men, the doll (who came into existence in 1955) was herself a plaything — a masculine joke, perhaps, for West German males who could not afford to play with a real Lilli. A German brochure from the 1950s confided that Lilli (the doll) was ‘always discreet,’ while her complete wardrobe made her ‘the star of every bar’.”

Guinevere in California: “My son Anthony (13 years old) came home from school describing a ‘lawsuit’ his teacher told him about. It was the Winnebago-cruise control legend. I told him sorry, but that’s an urban legend and directed him to your site (and Snopes.com). He printed out the respective pages and showed them to his teacher. She was surprised to find that [the case] was false and he received extra credit. As an aside, shortly afterwards the dentist informed me that he had five cavities(!) His reply, ‘Don’t worry about the bill, Mom. We can sue the candy companies’ (tongue firmly in cheek).”

Watch him, Guinevere; he’d make a vexatious lawyer!

Last…

Here’s Aqua’s official Barbie Girl video, which as I post this has 758.1 million views:

- - -

Email Subscriptions

No new cases are being published, so please don’t try to submit cases.

My Flagship Email Publication This is True continues to come out with new stories every week. It’s “Thought-Provoking Entertainment” like Stella, but uses weird-but-true news items as its vehicle for social commentary. It is the oldest entertainment newsletter online — weekly since 1994. Click here for a This is True subscribe form.

Perfect.

In 2015(?), PostModernJukebox did a fantastic cover of “Barbie Girl,” rearranging it to a Beach-Boys era song. If you haven’t seen it, check it out on Youtube.

—

While I’m familiar with PMJ and have seen many of their videos, I hadn’t seen that one! It’s in a “Beach Boys style” and is hilarious, especially the choreography (and Morgan James looks the part and sings the song REALLY well): PMJ Barbie Girl cover. The 2015 video is coming up on 14 million views. Thanks for the heads up! -rc

The song wasn’t much but loved the next 5 seconds after the song ended.

—

Yeah, I wouldn’t want to hear it very many times — but those 5 seconds made me laugh! -rc

“It didn’t help that the song’s catchy tune made it easy for those same young girls to memorize every word.”

Only young girls? At the time there were that many radio stations around the world that were banging it out (pun intended). I think a lot of guys do too. OK perhaps not all the words but a sizeable chunk.

—

The song seems clearly aimed at young girls, but *shrug* — not sure why that’s worthy of nitpicking. -rc

Nerf is a trademark owned by Hasbro, and is another good example of “a mark with a meaning beyond its source-identifying function.” Among video game players, nerf has become a term for when a game company reduces the effectiveness and/or fun of something in the game.

—

For that matter, so is “spam”! Hormel didn’t like it one bit, but there’s truly nothing they can do about it. -rc